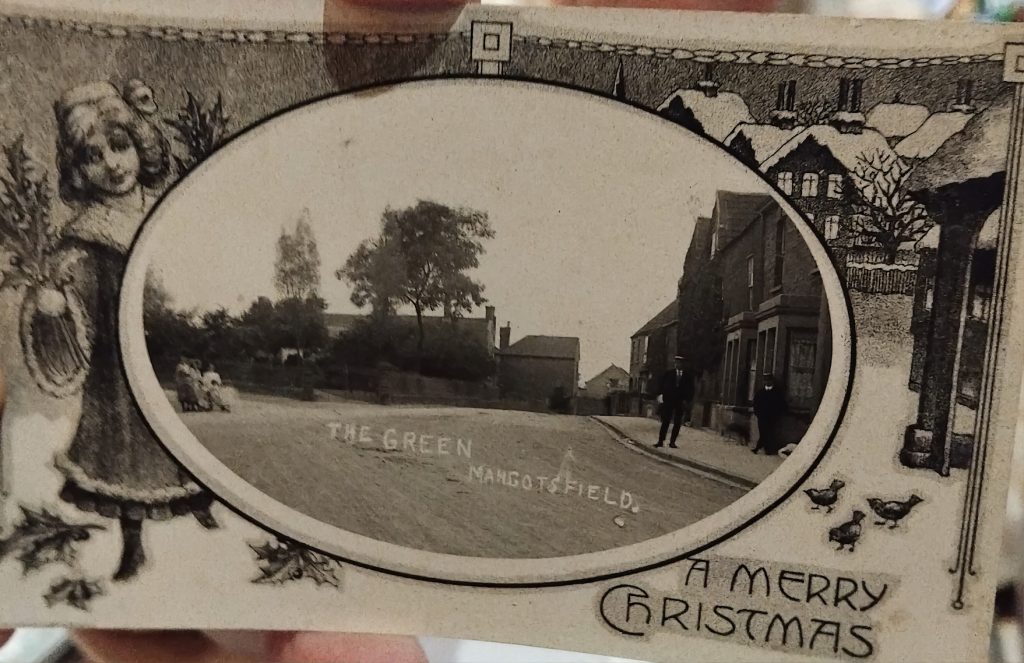

History captured on a postcard

WE communicate constantly nowadays, but before we had access to phones, instant messaging, texting and emails, people relied on letters, telegrams and postcards to stay in touch.

Letters, sealed in envelopes, were the main form of communication for centuries.

They were often written in formal language, with correct ways to address and sign off, and they took care and effort to write. The time they took to arrive varied, as they were delivered by person, horse or carriage – from hours in big cities with frequent mail services, to weeks or months internationally.

Telegrams were introduced in the 1830s, providing a novel and rapid way to communicate. This didn’t entail carrying a physical object like a letter, but sending the message electronically via an operator based in a telegraph office, usually in Morse code.

These were transmitted within an hour or a day but they were expensive, charged by the word, so senders kept them short and terse.

They were often used to convey urgent bad news, like war casualties, or good news like birth announcements.

In 1870 the first British postcards were made (based on an Austro-Hungarian idea which had proved extremely popular a year before).

Costing half as much as a letter to post and arriving quickly – with several collections and deliveries a day – they caught on fast.

People could dash off a cheery message or share news quickly without having to spend time drafting a full letter and finding an envelope and stamp before posting it.

The first postcards had an imprinted, pre-paid stamp and space for the address on one side, with the other side left blank for messages.

Postcards were used for frequent, informal chat, for sweethearts to send romantic messages to one another, to arrange get-togethers, send short pieces of news, or Christmas, Easter and other greetings.

During the two World Wars soldiers and prisoners of war were given free postage, so they could reassure their families that they were safe.

By the end of King Edward VII’s reign in 1910, an incredible 800 million postcards were being sent every year.

Over time postcards changed: by 1902 most had a printed picture on one side, with both the address and message squeezed onto the reverse.

This was a boon to photographers, who could produce local cards, although most were printed. Before D-Day, a request for photos of the French coast swamped the military planners with over 10 million cards.

It became customary to send postcards from your holiday to friends and family, showing them scenes of what they were missing.

In 1968 first and second class postage rates were introduced, and it cost the same to send a letter or a postcard, so their popularity declined.

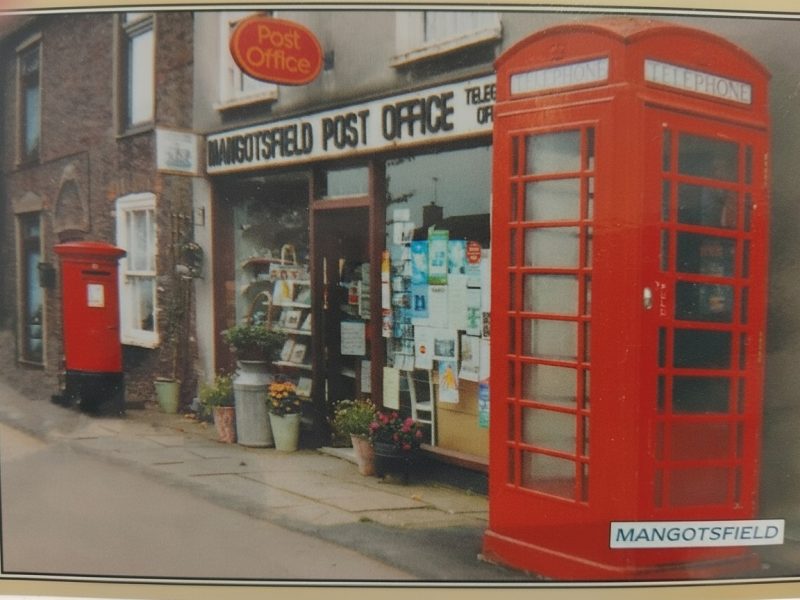

They are still sold as souvenirs today, and are fascinating collectibles that reveal how places have changed over time, like the views of Mangotsfield pictured on the examples here.

Downend Community History and Art Project (CHAP) is a not-for-profit voluntary organisation that aims to produce a community history resource and create a coherent identity for Downend and Emersons Green, built around interesting or significant places, people and events from the past.

To get in touch visit www.downendchap.org, email big.gin@yahoo.com or write to CHAP, 49 Overnhill Road, Downend, Bristol, BS16 5DS.

Helen Rana