Wind power, 1820s-style

TODAY we use wind power for energy, but two hundred years ago a man in Bristol was experimenting with using wind for mobility.

George Pocock (1774–1843) was an inventor, innovator and original thinker.

He even came up with a new approach to religion, making a tent big enough for 500 people to take a more evangelical form of Methodism to people around South Gloucestershire and North Somerset. This became known as ‘Tent Methodism’ and got him and his co-preachers expelled from the Wesleyan Methodists, but it only lasted for a few years (1814-1819).

Pocock was already busy with other things. As well as working as an English teacher at a school in Prospect Place, and being married with 11 children, he was fascinated with kites and their potential uses.

He experimented by trying to pull stones and then planks with kites, explaining: “I wondered and I grew ambitious.”

He certainly did, going on to use kites to lift his pupils and his own son high up into the air.

In 1824, his daughter Martha, sitting in a wicker chair, was hoisted 270ft up over the Avon Gorge with a 30ft kite!

Thankfully she survived, and grew up to become the mother of famous local cricketer WG Grace.

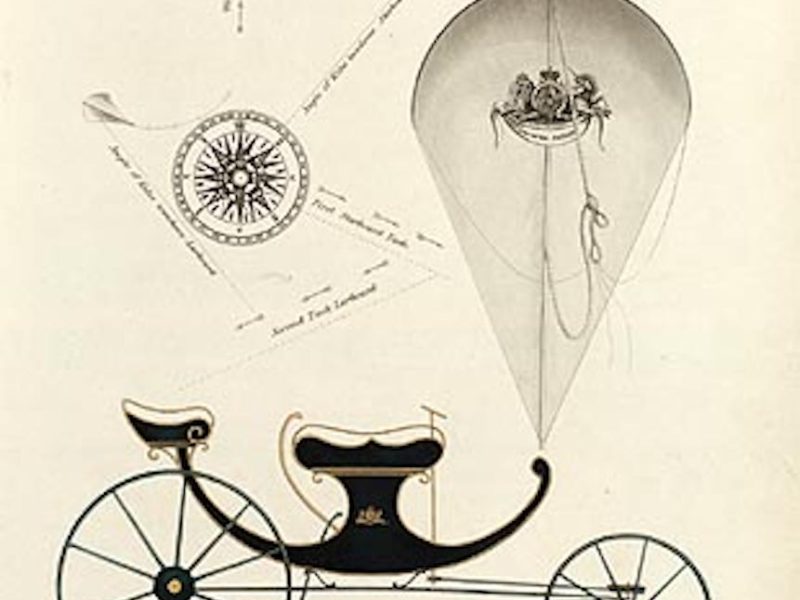

Next, George worked out how to pull vehicles with kites, and in 1826 he patented the design for his ‘char-volant’ buggy (from the French words for carriage, char, and kite, cerf-volant).

This used two kites to pull along a carriage carrying several passengers at up to 20mph.

There were four control lines for the kites, a T-bar to steer the front wheels, and an iron bar to drop down with a lever, for braking.

Unsurprisingly, these novel kite-drawn carriages were hard to control, so they never caught on – even though Pocock promoted his invention as being cheap to run, because drivers wouldn’t need horses to pull them, or have to pay toll charges for ‘horse-drawn vehicles’ at turnpikes.

George had lots of other ideas for using kites, such as providing auxiliary sail power for ships, as a way of dropping anchor and helping with rescues from shipwrecks.

Sadly, no charvolants have survived, but the Museum of Bristol does have one of his kites.

Downend Community History and Art Project (CHAP) is a not-for-profit voluntary organisation that aims to produce a community history resource, a coherent identity for Downend and Emersons Green and encourage the local community to take part in its activities.

For more information visit

www.downendchap.org.

Helen Rana